- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

On Well-Ordered Societies Fulfilling the Difference Principle

Takashi Suzuki*

Department of Economics, Meiji-Gakuin University, Japan

*Corresponding author: Takashi Suzuki, Department of Economics, Meiji-Gakuin University, Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Submission: August 28, 2018 ;Published: September 06, 2018

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume2 Issue5

Introduction

The difference principle which was proposed by John Rawls [1] as a principle of social justice states “Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are attached to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged (p.83). Rawls [2] listed up to five kinds of social regimes:

a.laissez-faire capitalism.

b.welfare-state capitalism.

c.state socialism with a command economy.

d.property-owning democracy.

e.liberal (democratic) socialism.

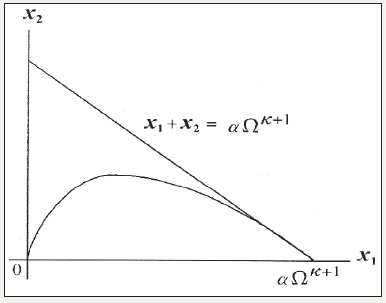

figure 1:A Theory of Justice, p.76.

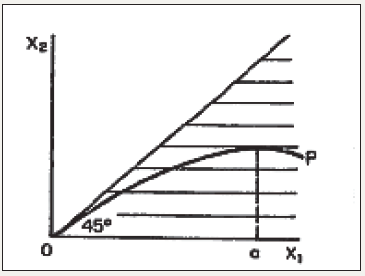

Asked himself “When a regime works in accordance with its ideal institutional description, which of the five regimes satisfy the two principles of justice?” He eliminated regimes (a) to (c) because he felt that they violated the principles of justice from the outset and concluded: “this leaves (d) and (e) above, property-owning democracy and liberal socialism: their ideal descriptions include arrangements designed to satisfy the two principles of justice (ibid., p.138). However, Rawls did not provide any positive or convincing proof to demonstrate that the second principle was indeed satisfied within (at least) these two regimes. Indeed, his theoretical explanation is far from satisfactory, “Suppose that x1 is the most favored representative man in the basic structure. As his expectations are increased so are the prospects of x2, the least advantaged man. In Figure 1 let the curve OP represent the contribution to x2’s expectation made by the greater expectations of . x1 The point O, the origin, represents the hypothetical state in which all social primary goods are distributed equally. Now the OP curve is always below the 45-degree line, since x1 is always better off. Thus, the only relevant parts of the indifference curves are those below this line, and for this reason, the upper left-hand part of Figure 1 is not drawn in. Clearly, the difference principle is perfectly satisfied only when the OP curve is just tangent to the highest indifference curve it touches. In Figure 1 this is at the point a ([1], p.46).”

The purpose of the present note is to provide a rigorous proof of Rawls’s claim and to discuss the conditions required for the difference principle to be fulfilled in well-ordered societies in the sense of Rawls [1-3]. We will see that Rawls’s theses, which are presented in his books, are essentially all valid, hence the difference principle is an acknowledged principle of social justice.

Toy Model for the Difference Principle

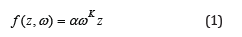

We aim to identify the mechanism that generates the contribution curve OP. The eminent feature of the curve is the rising portion in which some sort of mutual benefit or reciprocity should operate. This can be most simply provided by a production function with external increasing returns [4-6], such as

where z denotes the quantity of inputs, α and κ are positive constants and ω is a parameter that represents the (share of) “primary good” in the Rawls sense [1] as explained below. Notice that productivity increases with the value of ω. We interpret this in such a way that the primary good, operating through background institutions such as family, education, media and other social or political systems, increases productivity. The positive externalities indicated by the parameter ω convey the idea of reciprocity between society and individuals as producers. We call the constant κ≥0 the degree of reciprocity. Explaining the contribution curve by introducing externalities accords with the following statement by Rawls: “Note that the contribution curve, the curve OP, supposes that social cooperation defined by the basic structure is mutually advantageous. It is no longer a matter of shuffling about a fixed stock of goods ([1], p.77).”

Suzuki [7] constructed a socio-market model based on the production function (1), which satisfies the difference principle described by Rawls. As it is endowed with an economic market as its basic institution, our model represents a property-owning democracy or liberal (democratic) socialism. We assume that two kinds of goods are traded in markets. Consumption goods are consumed by all members of society and the amount consumed is x. Consumption goods determine the current quality of life of citizens and influence their expectations of their future lives. The other type of good is primary goods, which are used as an input (resource) to produce the consumption goods and are denoted by z. The primary goods are not consumed, which means that the consumers’ utilities do not depend on it. Therefore, the value of the consumption goods equals the utility level from consumption if we restrict ourselves within the class of monotonic and continuous utility functions. This allows us to avoid the problem of the interpersonal comparability of utilities. As stated above, the primary good also serves to develop the ability of citizen 1, which operates through the background institutions and enters the model as a positive external effect and finally is used as “money” to purchase the consumption good. For simplicity, we assume that there is initially no consumption good in the society (market) and so it must be produced by the social cooperative production activity described as follows.

There are two groups of citizens (consumers). Citizen 1 represents (the group of) more-advantaged (or talented) person(s) in the sense that she owns the production function (1) and citizen 2 represents (the group of) less-advantaged person(s) who does not. A natural interpretation of (1) is the presence of potential ability such as natural talents. However, it reflects the background institutions explained before; therefore, its interpretation should not be restricted to natural talents. Instead, it will include one’s own environmental elements such as family and education. As for the latter, while opportunities in education are certainly open to all citizens in liberal societies, they must choose (and be chosen by) an appropriate school (such as schools of law, medicine, engineering, and music). The production function, in this case, results from a combination of one’s natural talent and school education.

Citizens own nothing but possess some amount (possibly 0) of the primary good as an initial endowment. Let Ω (>0) be the total amount of the primary good that initially exists in society. We denote the share of citizen 1 by ω; therefore, the share of citizen 2 is Ω- ω. We identify ω as the index of the policy parameter, and search for its value that achieves the social state in which the difference principle is satisfied.

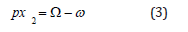

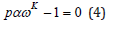

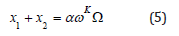

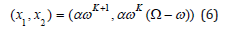

Let p be the price of the consumption good and we normalize the price q of the primary good as q=1. The budget equations of both consumers are then given by

where x1 is the consumption level of citizen 1 and x2 is that of citizen 2. As the production function is of degree 1 (constant returns) in z, the profit should be 0,

Given the primary good is not consumed, we can set z= Ω at the equilibrium, hence the market condition is given by

The equilibrium consumption levels are easily calculated from (2) through (5) as follows

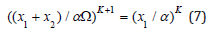

Normally, we would expect that x1≥x2, but not always (see below). Eliminating w from equation (6), we obtain the contribution curve

When we graph equation (7) in the x1- x2 plane, we obtain a concave and single-peaked curve similar to that in the previous section, see Figure 2.

figure 2:The case of k > 1.

Rawls set forth that “[t]he point O, the origin, represents the hypothetical state in which all social primary goods are distributed equally.” Hence point O in Figure 1 corresponds to the point associated with ω=Ω/2. The latter yields the point where the curve and 45-degree line intersect in Figure 2. Hence, strictly speaking, the contribution curve is then the region north-east of the curve obtained from (7). Rawls also stated “the difference principle is a strongly egalitarian condition in the sense that unless there is a distribution that makes both persons better off (limiting ourselves to the two-person case for simplicity), an equal distribution is to be preferred. The [social] indifference curves [...] are actually made up of vertical and straight [horizontal] lines that intersect at right angles at the 45-degree line [...]. No matter how much either person’s situation is improved, there is no gain from the standpoint of the indifference principle unless the other gains also ([1], p.76).” This means that each equilibrium point on (7) should be normatively evaluated by the social welfare function W(x1 , x2 ) = min{x1 , x2 } ≡ x1 . The next theorem can be readily verified.

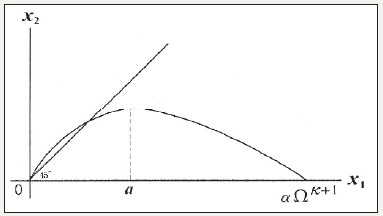

figure 3:The case of k < 1.

Theorem 1: For κ>1, the value of the social welfare function W(x1,x2)is maximized at the highest value of the least advantaged persons x2 (the point x1=α in Figure 2).

Justifies normatively the difference principle for societies with the degree of reciprocity sufficiently large (at least greater than 1). However, when κ is smaller than 1, the situation would be somewhat different, see Figure 3. In this case, the peak lies above the 45-degree line and the least advantaged persons consume more than the talented persons. This state of equilibrium is not considered just, or rather.

figure 4:The utilitarian principle.

Theorem 2: For κ>1, the value of the social welfare function W(x1,x2)is maximized at the highest value of the least advantaged

persons x2 (the point x1=α in Figure 2).

Perfect equality is recommended as a just distribution for

societies with insufficient reciprocity. We recall that the utilitarian

principle aims to maximize the total (or average) utility x1+x2 (or

The next theorem might look surprising.

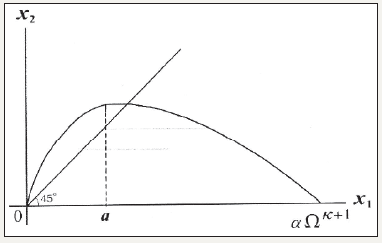

The next theorem might look surprising.

Theorem 3: For all κ ≥0, x1+x2 is maximized for (7) at 1 (αΩ^(κ+1) , 0).

Theorem 3 is illustrated by Figure 4 and proved by calculating the derivative of the curve from (7) at (αΩ(κ+1),0) see [7],for details.

The utilitarian principle insists that the state where the advantaged persons monopolize all is just! This claim seems intuitively absurd; indeed social welfare at this point is the least among all possible values, or equal to that of the origin,W(αΩ(κ+1),0)=W(0,0)=0.

Well-Ordered Societies Compatible with the Difference Principle

What conditions are required for societies to satisfy the difference principle? As this is a question concerning political philosophy, the economic considerations in the previous section are not enough. To answer this question, we must examine both the political and economic considerations. Indeed, examining only the economic perspective might result in misinformed political discussions. For instance, in the previous model, it can be readily seen that an allocation (x1,x2) is Pareto optimal if and only if x1,x2 = αΩ(κ+1) Then, the allocation (αΩ(κ+1) ,0) is the only Pareto optimal allocation on the contribution curve from (7). If we only consider optimality or efficiency in the market results, then the maximal economic difference is a desirable state for society! We have to distinguish the virtues of rationality and efficiency in economic markets from those in the political domain such as reasonableness and justice. Here, we are concerned with the latter.

We have to also correctly take into account the economic results in the previous section. What are the lessons of those theorems? Theorems 1 and 2 require a sufficient degree of reciprocity. The natural interpretation of the model suggests that this can be achieved by social and political supports for families, promoting the educational system and media, facilitating information network systems, and so on. These are institutions that produce mutually beneficial outcomes or reciprocity between citizens. Although economic markets are certainly an institution for the mutual benefit of traders, they do not guarantee the fulfillment of the difference principle. Building, provisioning and maintaining those fundamental institutions are important tasks of governments and societies because they are the social basis of the difference principle. Rawls stated “the difference principle expresses a conception of reciprocity. It is a principle of mutual benefit ([1], p.102).”

Even if the basic institutions are established, the difference principle cannot be satisfied automatically. The government would have to conduct some fiscal policy, for example collecting taxes, to achieve an allocation with an economic difference permitted by the principle. First, suppose that citizen 2 initially owned all the resources, which were taxed by the government. The citizen would do so whenever he/she is rational because the tax will be used to make them better off. In contrast, consider the situation where all resources are initially owned by citizen 1. How is this possible? It is difficult to assume that the citizen will agree to pay tax voluntarily if he/she is rational, as is usually assumed in economic theory. The government will be able to collect money only through some law that coerces the citizens to pay taxes. For the citizens to endorse this law, the difference principle must necessarily be already accepted in society as a principle of justice. The citizens must also be convinced that the government’s fiscal policy will execute the difference principle. Furthermore, the citizens must hold these facts as public information.

Rawls required for the society to be well ordered, “its citizens have a normally effective sense of justice and so they generally comply with society’s basic institutions, which they regard as just ([3], p.35).” However, for this condition to be satisfied, it seems insufficient that the citizens are simply rational. Instead, they must be reasonable. That is, citizens are “ready to propose principles and standards as fair terms of cooperation and to abide by them willingly, given the assurance that others will likewise do so.” We recall that the productivity of citizen 1 is increased by external effects from background institutions, which means that they owe the improvement of their abilities to society. This yields fair terms of cooperation in Rawls’ sense: “We cannot view the talents and abilities of individuals as fixed natural gifts. To be sure, even as realized there is presumably a significant genetic component. However, these abilities and talents cannot come to fruition apart from social conditions, and as realized they always but one of many possible forms. Developed natural capacities are always a selection, a small selection at that, from the possibilities that might have been (ibid., pp.269-70).” When the citizens are reasonable rather than merely rational, the difference principle is self-supporting because society would have reasons to counterbalance the desire to violate its current terms of cooperation. Rawls described three reasons why the difference principle results in stability: “First, there is the effect of the educational role of a public political conception. Thus, we suppose all members of society to view themselves as free and equal citizens who, in and through the basic structure of their institutions, are engaged in mutually advantageous social cooperation. Given this conception of themselves, they think that the principle of distribution that applies to that structure should contain an appropriate idea of reciprocity ([2], pp.125-6).”

The second reason is as follows: “We also suppose that in addition to the reason which all have, the more advantaged have a second reason, because they are mindful of the deeper idea of reciprocity implicit in the difference principle when it is applied to the basic structure: namely, that it tends to ensure that the three contingencies [their social class of origin, their native endowments, the good or ill fortune] are taken advantage of only in ways that are to everyone’s advantage (ibid., p.126).”

The third reason is that the difference principle encourages mutual trust and cooperative virtues because it will make people understand that the three contingencies tend to be dealt with only in ways that advance the general good, and that constant shifts in relative bargaining positions will not be exploited to achieve goals motivated by self- or group interest.

These three conditions are natural observations of the mental attitudes of reasonable people in liberal societies which are considered a fair system of cooperation among free and equal citizens. We conclude that the difference principle would be possible and stable as the principle of justice in such societies where the fundamental institutions for serving reciprocity among reasonable citizens who recognize themselves as free and equal are established.

Acknowledgment

An earlier version of the paper was presented in the 76th annual meeting of the philosophical association of Japan held at Hitotsubashi University, May 20, 2017. This research is supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research (No.15K03362) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

References

- Rawls J (1971) A Theory of justice. Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, USA.

- Rawls J (2001) Justice as fairness: A Restatement. Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, USA.

- Rawls J (1993) Political liberalism. Columbia University Press, New York, USA.

- Chipman JS (1970) External economies of scale and competitive equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics 84: 347-385./a>

- Romer P (1986) Increasing returns and economic growth. Journal of Political Economy 94: 1002-1037.

- Suzuki T (2009) General equilibrium analysis of production and increasing returns. World Scientific, Singapore.

- Suzuki T (2018) A Simple model of the difference principle. Theoretical Economics Letters 8: 1869–1888.

© 2018 Takashi Suzuki. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)