- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

Objects in Transit and Objects in Storage; Cultural Heritage on Exhibit in the 21st Century

Catherine Mathias

Probability, Statistics and Modeling Laboratory, Sorbonne University, Canada

*Corresponding author: Catherine Mathias, Probability, Statistics and Modeling Laboratory, Sorbonne University, Lindsay, Ontario, Canada

Submission: August 28, 2018Published: September 19, 2018

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume2 Issue5

Introduction

This short note addresses the issues of where are our objects being exhibited in the 21st century. Additionally some basic reminders of preparing objects for movement and storage will be presented. Having worked in Afghanistan and Qatar, between 2012 to 2014, one becomes aware of the fact that objects move for reasons of both exhibit and terrorism. That said some of the objects used to fund terrorism do end up in the secular realm and on occasion on exhibit in a museum far from their original home. That said if said objects were left in the ground would they be safer; would they ever be on exhibit? Objects currently in survey museums around the world are now subject to deaccessioning policies, often not peer reviewed, and damage due to poor storage environments. Will these objects be available for exhibit in the 22nd century? These are questions that will possibly haunt the next generation of museum professionals however if we continue to remember the following basic method and theoretical approach to museum work perhaps we will have helped to make the next wave of museum work easie

Museum Moving

Some basic principles of shipping need to be applied when moving museum objects. Always use reversible materials and extra is better than not enough. Hence when shipping a group of paintings and works of art on paper from British Columbia to Ontario and back it was decided by the Victoria County Historical Society to ship via Purolator and tape any glaze; apply tissue and microfoam around object; box individually and then crate boxes and ship. This methodology, though crude, worked well and all objects arrived safely. Based on experience working in Afghanistan in 2014, art and artifacts are possibly one of the most vulnerable and mobile aspects of culture at this time. I have witnessed the destruction of culture, and found artifacts displaced from their home of manufacture, not through the normal process of a travelling exhibit. Such movement negates the normal museum care and hence such material culture has suffered greatly and in some cases can no longer be recognized without scientific analysis.

From a conservation perspective some of these objects, though not in their original context, are possibly better preserved. For example the 1978 hoard of gold from the Tillya Tepe, Afghanistan, now on exhibit at large survey museums around the world has the best security and conservation practices available. But what of those objects that slip through the cracks so to speak? Where do they end up? If movement of people and money was not so easy would these objects have left their country of origin? Also, is it only the war zone which should be the focus here? What about other countries with significant cultural heritage such as Mexico? What about our own country, Canada? Prehistoric lithic arrow heads have been looted from sites in Southern Labrador since the early 1980s? Where are those objects now?

One would not think that after years of both experience and educational training the most difficult challenge in a somewhat glamourous museum job would be moving objects from one place to another. However the movement or transit of cultural heritage is multifaceted. First you have the physical damage. As soon as that fragile vase is lifted from its support mount in a climate conditioned storage environment the physicochemical impact on the object increases. The human body of the conservator lifting the object creates a high moisture level close to the object in addition to other toxins such as acids and a variety of aromatic scents. Next gravity kicks in and if all goes wrong the object drops and is irreversibly changed for life (Figure 1).

Budget and Time-Line

One of the mysteries of the cultural heritage sector, after working in the scientific sector, is the ideology that money grows on trees. Many people have grown up in this sector having money thrown at them for projects. Those days clearly are ending in most parts of the world and we too must change with the times. Though people are hesitant about grant proposals they generally are designed to write for themselves and therefore before you begin your project check to see if you can obtain a bit more money for it. Money will make any moving project easier, more time efficient and fun.

Figure 1:Mangled avionics from a B24 crash site during WW11 at the Gander, NL, Canada, airfield. An example of mass damage done by gravity.

Documentation for Moving

Documentation within the museum field is always welcome and vital. Never underestimate the value of a photo, sketch or written note on the condition, location, history or value of an object. That said try to maintain an organized database and archives. This should also been compiled for any moving event. Photo documentation should be a requirement from start to finish but is not always requested. Accidents can and will happen therefore document with care.

Location Details from Where to Where

Before putting in the renovations or moving to a new building think about how the collection will move and fit into the new space. Often buildings are selected or designed without taking into consideration the objects and how they will like the new space. A move could be based on the fact that to bring in more visitors or to make the organization visible in the community a more central location is required or a fancy new design for the building. That said the objects may not like the move and the pros and cons of their needs should be accounted for before moving forward. The logistics of the move is something all museum personal are well trained to figure out and execute. One important point is to have the collection ready to go. That said in one move of more than 1,000,000 archaeological artifacts the collection was not ready and had to be shipped as is. In this case objects were left in storage trays with packing put around them, covered with microfoam and packing tape to secure packing materials. Ironically the objects moved safely and this saved both money and time. Unfortunately the link between object location and the database was lost and most had to be re-examined and catalogued. Hence this strategy ends up being quite expensive and should be avoided. That said it is nice to see it can be done. The quick thinking of the author, then conservator for the organization, based that packing strategy on work by Stefan Michalski, in which if you isolate the object and render it unable to move in packing that is less rigid than itself, the risk to physical damage is almost eliminated.

Transportation Details

These details are the specifics. For example if you are moving objects in a large city perhaps ask for police escorts and have the final off-loading destination reserved. This will make for a timely move with the objects in a foreign environment for as little time as possible. Also research the type of moving vehicle which will be used. Also investigate the experience of the movers.

How does this Affect Researchers and Museum Visitors

When one plans a move of a large collection of objects the impact on the museum is high. The move itself is often designed because it will enhance the overall operations of the museum. That said as this type of operation is significant it can also distract from the museum in a way that is lasting. For example some of the larger survey museums in Canada have in the last decade undergone significant alterations some of which have driven both visitors and researchers from the institute. Some of the anger behind this has been the fact that collections were no longer accessible or people have travelled a great distance to view collection on exhibit which were no longer on exhibit. Rare is it to find a museum such as the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam where much of their funding comes from the footballers who visit during their playing season. This type of visitor does not mind disruption of any sort and is only seeking minor entertainment and some good gifts for the family at the gift shop, conveniently situated at the end of most exhibits. Therefore before starting to pack have a detailed plan that helps to make the process fast and easy for all people involved with the institute. One object group would be ruins within an archaeology site. Here the objects remain permanently available unless destroyed by war or environmental changes. Perhaps these are the object group of the 22nd century (Figure 2).

Figure 2:View of mansion house from a 17th century plantation site in Ferryland, Newfoundland, Canada. This object group has survived burial from the 1600s and will now survive many years above ground. The building stone was created some 500 million years ago.

The following objects are from the Ferryland archaeological site in Newfoundland, Canada. Note the high quality of preservation. If we can keep archaeological sites from being looted, those objects will be available for the next century and largely well preserved. In fact most burial environments are far superior to anything in a storage or exhibit environment (Figure 3-11).

Figure 3:Silk embroidery from the mid 1600s, Ferryland, Newfoundland, Canada

Figure 4:Barrel staves from Ferryland, Newfoundland, Canada. Note the high degree of preservation is due to a high water content in the soil matrix.

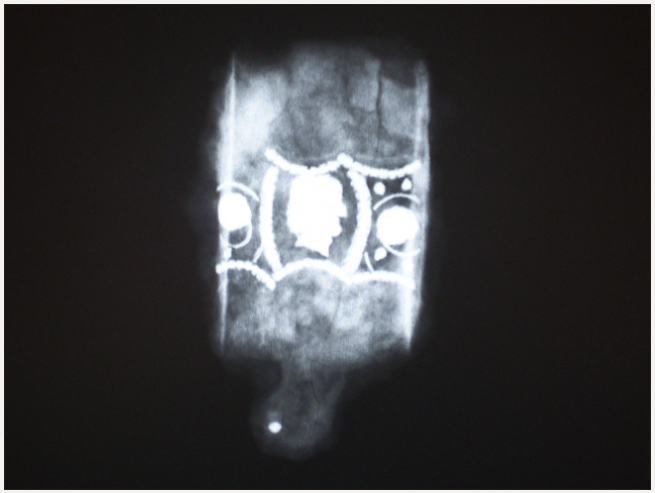

Figure 5:X-radiograph of a snuff box from the 1600s, Ferryland, Newfoundland.

Figure 6:Maker’s mark on barrel stave from the 1600s, Ferryland, Newfoundland, Canada.

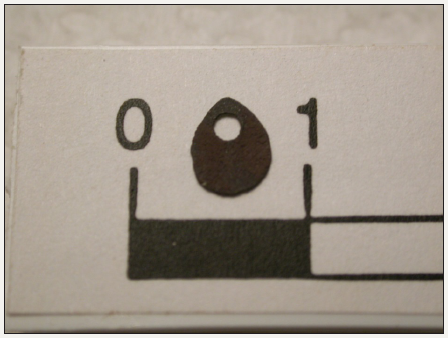

Figure 7:Spangle made of silver from the 1600s, Ferryland, Newfoundland, Canada.

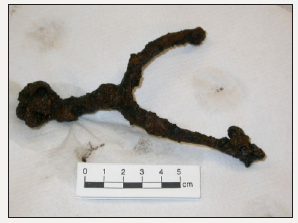

Figure 8:Iron bootspur from the 1600s, Ferryland, Newfoundland, Canada.

Figure 9:Parachute from a WW11 crash site of a B24, Gander, Newfoundland, Canada

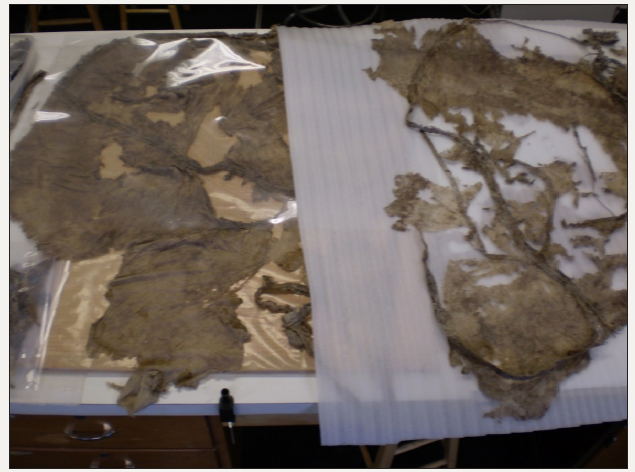

Figure 10:A group of shoes made of leather from the 1600s to the 1800s. Note the high degree of preservation is because of the moisture content and tannins in the soil matrix.

Figure 11:Some damage does occur in the burial environment due to weight of surface soil. Ceramic vessel from the 1600s, Ferryland, Newfoundland, Canada.

Conclusion

All working within the museum sphere should think carefully about their collections and remember the basics of museum theory.

© 2018 Catherine Mathias. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)